Amaarae recently made history as the first Ghanaian solo act to perform at Coachella: one of the most iconic music festivals in the world. Midway through her set, she paused to spotlight Ghana’s rising alté(rnative) music scene, name-dropping the likes of Joey B, collectives like La Même Gang and the Asaaka Boys, and skipping the usual list of legends to shoutout a woman – Eazzy – whose Wengeze was recently given a facelift by Bree Runway (coincidentally touring with Amaarae soon). Calling herself a Black Star, she even introduced her global hit, “Sad Gurlz Luv Money,” as “the biggest Ghanaian song of all time.”

By morning, social media was aflame.

While some celebrated her for waving the flag, others accused her of performativity; of wrapping herself in Ghanaian identity only when it suits her. As with most things involving music and identity, there’s a lot to unpack. But at the heart of this backlash lie a few familiar chords: the uneasy relationship between home and abroad, between Ghana and its diaspora, and between authenticity and appropriation.

Let’s be very clear: Amaarae is exactly who she says she is. Her 2023 album Fountain Baby was the highest rated album in the world on Metacritic that year. When her single with Moliy and Kali Uchis, Sad Gurlz Luv Money blew up in 2021, it became TikTok gold, hit Spotify virality, and was, for a moment, the most Shazamed song on earth. Her claim that it is the biggest Ghanaian song of all time may come from an American metric: it is the highest-ranked Ghanaian song on the Billboard 100 chart since Osibisa back in the Seventies. The song was awarded Record of the Year at the Ghana Music Awards for the achievement.

And yet, many in Ghana still don’t know who she is.

More interesting however are those who do, and still refuse to claim her. They say that her flag-waving is hollow and her shoutouts are strategic. These accusations echo a broader diaspora discourse: the belief that Ghanaians abroad come home once a year for Detty December, wave the flag on the ‘Gram for Independence Day, but remain absent from Ghana’s lived struggles.

A Ghanaian-American national who was born in the Bronx and raised between Atlanta and Accra, Amaarae is a child of many worlds. Her dual citizenship is both a passport and a paradox. In one sense, she might be compared to Nigerian superstar Davido, who is also a dual American citizen. To some, his brand feels more immediately tethered to Nigeria than Amaarae’s does to Ghana. But the comparison doesn’t hold much weight: while Davido’s appeal is firmly rooted in mainstream Afrobeats, Amaarae is – by any definition – alternative as fuck.

Her sound doesn’t sit neatly in Ghana’s sonic memory bank. She doesn’t make highlife, hiplife, azonto, or sing in Twi (or any of our many other indigenous languages), besides a loose line here and there. Some even assume she’s Nigerian – Amarachi! – because that’s where she first blew up. Her sonic world does sometimes feel closer to Lagos and Los Angeles than it does to Labadi. Yet her music is not afrobeats in the Wizkid or Burna Boy sense. It is sensuous, genre-fluid, and global-facing. And she takes pride in transcending categories.

Both in and out of music, Ghanaians do at times other our own, and the politics of class is often at play in the way we receive alté(rnative) artists. Think of Sarkodie’s 2016 jab at Manifest: “obi bɛ diss me a, na ɛnyɛ rapper a ɔde GTP ntoma pam kaba.” There was a lot more going on there than an argument over wax print clothing.

A GIS alumna and the daughter of an industry titan, Amaarae is not beating any accusations of having enjoyed more privilege than many Ghanaians. While Ghanaians often aspire to wealth, we sometimes cast those who already have it as distant, unfamiliar, and even foreign, unless they make extra efforts to prove that they are not. That’s why, when someone calls you dadaba or dbee, the expected response isn’t acceptance but a kind of performative denial.

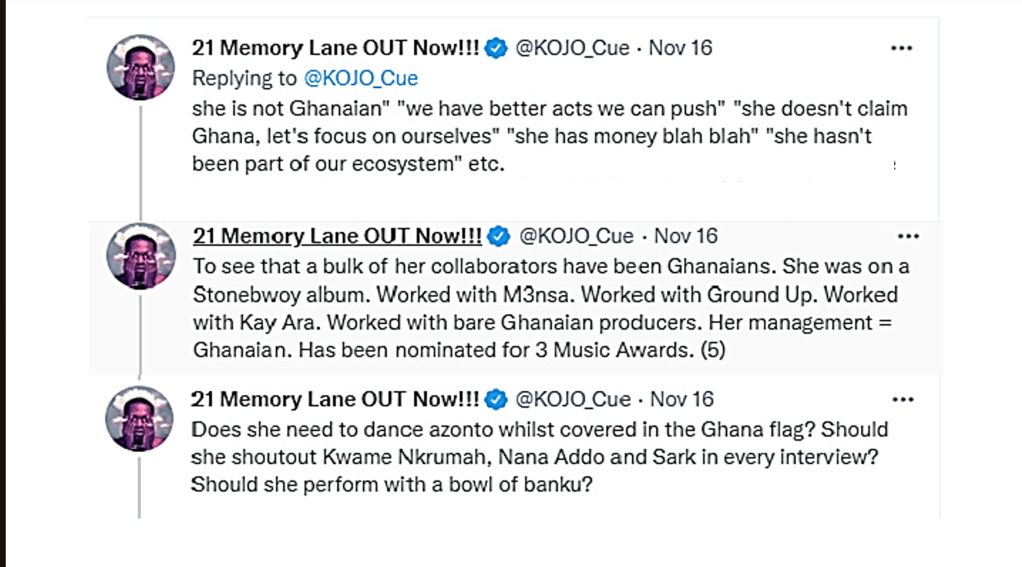

A few years back on Twitter (sorry, but I refuse to call it X – tcheew), one of my favourite musicians – Ko-Jo Cue – summed up the criticisms levelled against his fellow artist: “She’s not Ghanaian.” “We have better acts.” “She doesn’t claim Ghana.” “She has money.” “She hasn’t been part of the ecosystem.”

But does that ecosystem support artists like Amaarae? And what does Ghanaian even mean?

Ghanaian identity is often policed by accent, ideas, and aesthetics; as if there’s a single way to sound, to look, to belong. As if Ghana itself didn’t emerge from a tangle of languages, migrations, and influences.

Kwame Nkrumah once defined “Ghanaian” not merely as someone born within our borders, but as anyone born to Ghanaians anywhere in the world, especially if they are committed to ideals of freedom, justice, and African unity.

Keep that definition in mind for later.

Ko-Jo Cue also pointed out that Amaarae has collaborated with Ghanaian acts (including Stonebwoy, M3nsa, Moliy, and Kay-Ara); worked with Ghanaian producers; and is managed by Ghanaians. “Does she need to dance Azonto wrapped in the Ghana flag… Should she perform with a bowl of banku?” he asked.

The answer, of course, is no. But the problem is deeper than just optics – and classism aside, the critiques do have a sharper edge.

There are two parts to Nkrumah’s earlier equation: born to Ghanaians + commitment to Freedom, Justice & Pan-Africanism. While half of that is Amaarae’s birthright, nationality is not the only way to measure belonging.

Responsibility matters too.

Amaarae’s gender fluid image has made her very artistic existence a bold statement, especially at a time when Ghana’s queer community has been under increasing (and frankly unnecessary) attack. But people do not remember Amaarae being particularly vocal during the likes of the Occupy Julorbi protests against corruption in 2023, or when illegal mining (galamsey) protests erupted last year and young Ghanaians were being arrested and jailed for demanding clean water and environmental accountability. To paraphrase what one of those arrested – Cedric – said after watching her Coachella performance: “At least Burna Boy pretends to care about what happens in Nigeria. Fountain Baby can’t even be arsed. She says they should ‘Free Thugger’ though. Today, she says she is a Black Star. Okay.”

In a global age where identity is often brand currency, people are quick to sense when they feel someone is cashing in without carrying the weight. The message from her critics is clear: if you’re going to wear the jersey, you can’t ghost the game.

And yet, a question:

How much does Amaarae owe Ghana anyway?

Ghana may have helped make young Ama, but it didn’t make Amaarae. Not enough Ghanaians championed her when she was bubbling under. Too few of our radio stations play her music. Many only looked up when the world told us she mattered.

Maybe the problem is not solely hers.

We want our artists to represent us, but only on our terms; to carry the weight of a country that didn’t always carry them. And when they finally make it, we find ways to push them from their pedestals. Remember your roots – even if we didn’t water them.

Ghana rarely nurtures the rise of any of its artists, especially its alternative ones. In fact, Ghana barely nurtures any of its youth. Many of those criticizing Amaarae for not repping Ghana enough would japa and drop the country for an American Green Card in a heartbeat. And they would be justified in doing so.

For many young Ghanaians though, belonging isn’t just about birthright or presence. It’s increasingly about solidarity, and who shows up when it counts. When artists are perceived to invoke Ghana in times of triumph, but stay silent during crisis, it feels less like love and more like branding. It’s the same charge levelled at cultural appropriation: love the look, but dodge the work.

Whether or not these accusations are fair, Amaarae is not the first artist to feel this tension. She won’t be the last. Music may have become borderless, but even borderless artists must reckon with where they choose to root. And although she has carved out her own lane, maybe that lane hasn’t always run through Accra.

We’re all still figuring out what Ghanaian identity looks like in the global age. And our artists play a role in that, having served thanklessly as our cultural ambassadors ever since Nkrumah took ET Mensah and the Tempos on international state visits.

Culture matters, and – love or critique her – Amaarae is a part of Ghana’s global story. A history making one at that. She may not owe us a protest anthem, but her voice is part of the chorus, whether you have problems with the melody or not.